Preston River - Sylvan Way

Basin : Preston River

Catchment : Preston River

River condition at the Sylvan Way site (site code: PR2PRES1, site reference: 6114020) on the Preston River has been assessed as part of the Healthy Rivers Program (Healthy Rivers), using standard methods from the South West Index of River Condition (SWIRC). The SWIRC incorporates field and desktop data from the site and from the broader catchment. Field data collected included the following indicators, assessed over about a 100 m length of stream:

- Aquatic biota: fish and crayfish community information (abundance of native and exotic species across size classes, general reproductive and physical condition)

- Water quality: dissolved oxygen, temperature, specific conductivity, and pH (logged in-situ over 24 hours) as well as laboratory samples for colour, alkalinity, turbidity and nutrients

- Aquatic habitat: e.g. water depth, substrate type, presence of woody debris and detritus, type and cover of macrophytes and draping vegetation

- Physical form: channel morphology, bank slope and shape, bioconnectivity (barriers to migration of aquatic species), erosion and sedimentation

- Fringing zone: width and length of vegetation cover within the river corridor and lands immediately adjacent, structural intactness of riparian and streamside vegetation

- Hydrology: measures of flow (velocity) at representative locations (compared against data from stream gauging stations within the system)

- Local land use: descriptions of local land use types and activities (compared against land use mapping information for the catchment)

This is the first assessment of this site using the SWIRC methods. At this time no previous assessments of river ecology had been reported.

Assessments are listed below:

- 2020 – summer (February 26-27 ): Healthy Rivers

At this site, water quality was also logged over an extended period:

- 2019-2020 (December-April): Healthy Rivers

Other departmental data: The Sylvan Way site is about 1.5 km downstream of gauging station number 611007 on the Ferguson River at South West Highway and about 15 km downstream of gauging station number 611004 on the Preston River at Boyanup. Both gauging stations are owned by the department and are currently monitored.

Search using the site code or site reference in the Department of Water and Environmental Regulation’s Water Information Reporting (WIR) system to find data for this site and nearby sampling points (flow, surface water quality, groundwater monitoring, department’s meteorological data). See also the Bureau of Meteorology website for additional meteorological data for the area.

Condition summary

A complete condition summary for this site has not been published. Please contact the department’s River Science team for further information (please provide the site code and sampling dates).

The image below indicates conditions at the Sylvan Way site in February 2020. February is within the Noongar season of Bunuru, which is generally the hottest and often driest part of the year.

Images are provided in the gallery at the bottom of the page to show general site conditions.

Species found in subcatchment

Species found at the site

Fish and crayfish

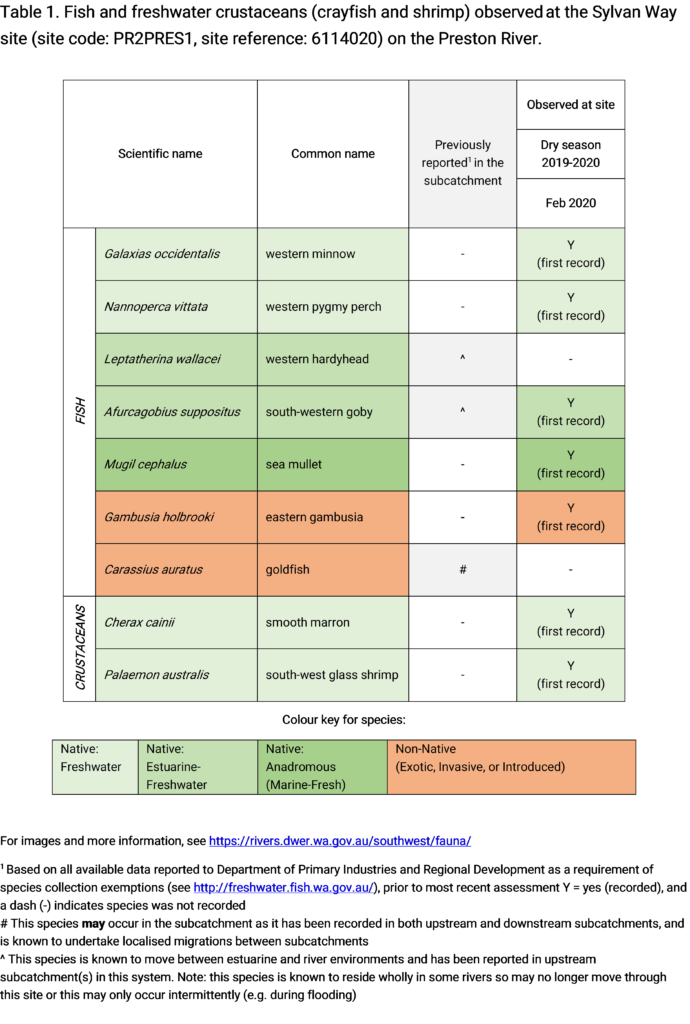

As this was the first time this site had been sampled using SWIRC methods, the species expected to occur here (listed below) are based on species reported from studies conducted elsewhere in the wider river catchment and our understanding of fish behaviour and movements within river systems. As differences in habitat within a reach naturally influence species distributions, and variability in methods between sampling programs can affect the species caught, this list is only indicative.

Note: collection of fauna from Western Australia’s inland aquatic ecosystems requires a license from the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) and also the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA). All species collected must be reported to these agencies as part of license conditions.

Only fish and freshwater crustaceans (crayfish and shrimp) that typically inhabit river channels are targeted by the standard SWIRC sampling methods. However, where other species were caught and/or observed (e.g., turtles, rakali-native water rats, tadpoles), these are mentioned below.

Other aquatic fauna

Westralunio carteri (Carter’s freshwater mussel) was observed at the Sylvan Way site during the assessment, see image below.

Westralunio carteri (Carter’s freshwater mussel) observed at Sylvan Way HRP, February 2020

This mollusc is the sole endemic freshwater mussel species in WA and currently listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) red list of threatened species, (due to declining range, which is largely attributed to the effects of salinity).